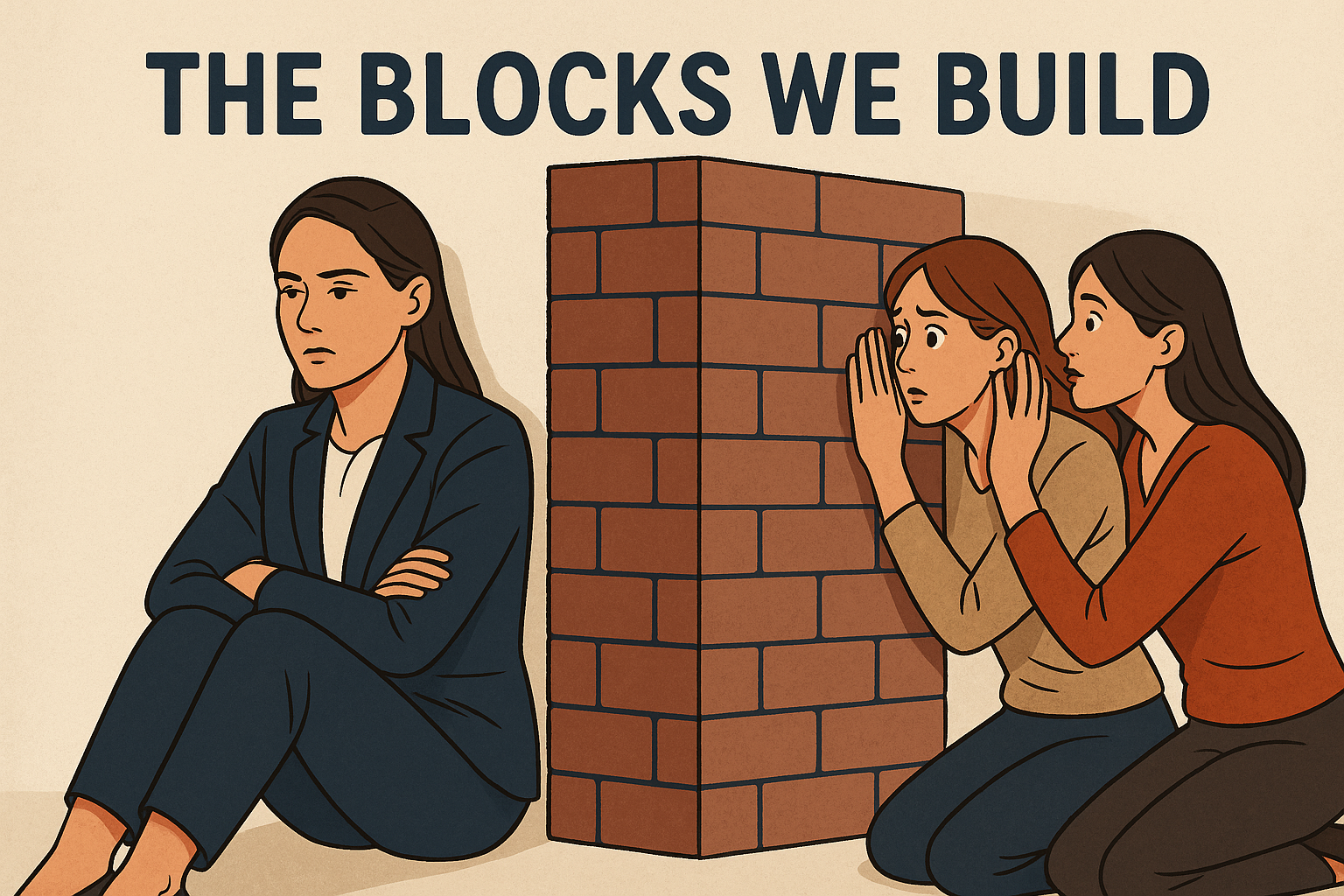

The Blocks We Build After High-Conflict Separation and Relationship Trauma

The mental blocks we form after high-conflict separation and relationship trauma often go unseen — sometimes for years. They are not always obvious. Most lawyers, therapists, counsellors, even those who work day in and day out through the family court system, miss these deeper wounds — wounds that become so intertwined into our minds, our bodies, and our nervous systems, that they start to feel like a part of us. They sink in like parasites, embedding themselves into how we think, how we feel, how we react — ready to appear the moment a perceived threat arises.

You may think you are fine. You may have survived the worst of it — the court process, the accusations, the conflict, the loneliness. You might have built a new life, a new routine. You may say to yourself, “I’ve moved on.” And then one day, you go on a first date, and — boom — it hits. Your body tenses. You overthink everything. You find yourself clinging too much, needing constant reassurance. Or you do the opposite — you run, you detach, you say “It’s too much, too fast.” Or you try to impress too hard, trying to win approval. You hear yourself say things that feel desperate, out of character. And then shame follows. You say “this isn’t me, I’m not like this”, I know you are not, it’s not the real you, the safe and secure you, and that ok.

If that sounds familiar — it’s okay. You are not broken. You are not self-sabotaging. You have developed a pattern to keep yourself safe — and it’s been working very well, even if it doesn’t always feel that way now. I want you to forget the term self-sabotage, you don’t want to hurt you, you want to keep yourself safe.

Some people never let go of past wrongs — they stay locked in anger, bitterness, frustration. Others go numb — shutting down emotions entirely. Both are ways of protecting. Some of the most extreme versions of this are seen in survivors of war, sexual assault, and deep childhood trauma. Gabor Maté tells of women who lived through such violence in war — seeing husbands and children massacred in front of them — who became literally blind. No physical cause could be found. The body shut down one of its senses to block out the unbearable. Other survivors of sexual assault may unconsciously make themselves less physically attractive — they let go of their self-care, they shut down their natural beauty, their compassion, their nurturing feminine energy, because that energy once brought danger. It is protection. The body remembers. If you have been abused, I want you to know it not your fault, you didn’t make them, you didn’t deserve it, it was their choice not yours.

In high-conflict separation, this process is not usually one single traumatic moment — it is slow, drawn out, a constant drip of stress and fear. It happens over months and years — during the court battle, the accusations, the financial stress, the loneliness, the isolation, the emotional attacks. Piece by piece, parts of us shut down. We learn patterns to stay safe — in the relationship, out of it, and in the court system itself. For some, especially where children are involved, these patterns become even more deeply wired. Protecting self — and protecting children.

These patterns become like armour. They stay long after the battle is done.

They often mirror attachment wounds from childhood. Children who received inconsistent love may develop anxious attachments. Children whose emotions were dismissed or ignored may develop avoidant attachments. Now, as adults, safety may mean controlling behaviours. It may mean setting rigid boundaries. It may mean avoiding closeness altogether. Or it may mean clinging to a partner, needing constant reassurance. New relationships may become a pattern of recoding financial efforts, and 50/50 effort for each. All these patterns may keep us safe, but they stop us from growing, they stop us from learning grace, and they keep us in survival mode, often missing the magic that new and healthy relationships can bring.

As love bombing becomes a hot term in separation it brings with it fears, that new love, love that genuinely wants to get to know you, that has the potential to remain grounded and hold space, even if you may be in a mess comes across as a signal to put up walls. And se we may push them away, not because we don’t want it, not because we fear love, but because we may either lose ourselves, lose our control and that means we may get hurt again.

All of these patterns are natural. They make perfect sense. But — they may no longer serve us if we truly want to grow, to move forward, to experience love again.

It is not about fighting these patterns. It is about recognising them, thanking them for keeping us safe, and allowing them to take on new roles as we heal. Because these old protectors — as strong as they are — can also keep us stuck. They can lock us into old cycles, old beliefs. They can stop us from reaching the life we truly want.

Our patterns do not do this because they wish us harm — it is the opposite. Subconsciously, these protectors believe they are helping. They are keeping us in what is familiar. They think: “Better this old pain than the risk of a new one.” We recreate old relationships, old environments, old habits, because they are known. Even when those old patterns were unhealthy, at least we know them — and knowing gives us some control. It gives us calm, of a kind. Our protector patterns keep us from not only the physical threats but from the emotional, our nervous system communicating to our amygdala, “we don’t want to feel these emotions again”. If I feel this emotion it may mean unsafety. Love may be mistaken for anxiety and fear from past relationships. It’s ok to feel this. But when a new love interest reacts with similar responses to us pulling away, we validate that we made the right choice, we feel calmer. It’s not until we meet someone that doesn’t react to our protector responses, that stays calm, that doesn’t chase, that gives us space and accepts us for who we are, that our confusion sets in and we may feel even more unsafe. It doesn’t feel like old patterns. You may have genuine feelings but push them away because now the new unknown may scare you more than the known.

We stick to the old. And when we try to make progress toward the new — fear arises. We fear the unknown. We cling to the old life. I have seen this with parents in the family court — fighting tooth and nail to hold onto an old life, an old identity, an old structure, even when it is already lost. They fight so hard for control — but in the process, lose their peace. The chaos spills onto their children. If we are not aware of our own behaviours, we may accidentally create the very patterns that harm our kids — patterns of fear, of control, of unsafe emotional environments.

A compliant child is not always a healthy child. If a child becomes compliant because it is the only way to feel safe — to meet the emotional needs of an unstable parent — this can plant deep wounds. A child who senses their parent will become upset if they express their own emotions learns to suppress their needs. And the cycle repeats.

This is why this chapter is hard. It asks us to look deeper — at the drivers beneath our actions. It asks us to meet our own protectors, and to give them new roles — roles that support growth, not just survival.

Ready to calm your mind and take control of your emotions after separation? Grab our 4-Week Coaching Program: Grounding Yourself After High-Conflict Separation for $35 - practical, compassionate, and made for this exact moment.